Monday, December 10, 2007

In conclusion

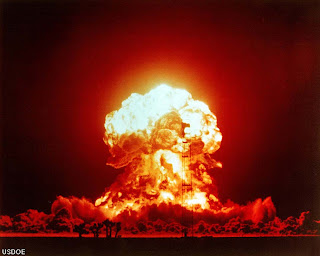

Postmodernity, multimodality, visuality, and atom bombs

In a recap of a conference on nuclear arms at the Wingspread Conference Center in Racine, Wisconsin that took place in Dec. 1983, Marian Rice writes about the inevitability of the intrusion of visual consideration into the argument on nuclear arms: "Richard Ringler, University of Wisconsin-Madison, demonstrated audio-visual material she has developed to show how the themes of war and peace have been treated in art, literature, and music. He stressed that it is necessary to approach nuclear weapons issues from a variety of viewpoints in order to reach students who might feel they do not have the background for a course which deals with technical topics" (8). Thus, the argument regarding nuclear technology might serve as an appropriate case study for the way in which visual rhetoric works as an effective accommodation to the ever-evolving needs of society at large. Whether one is utilizing visuals, art, literature, video, or some other medium, the function of argument can still work effectively. We should think of visual rhetoric not as a replacement of traditional argument, but as a complement to it, as a way of encouraging our students to think critically about a topic, even if they feel it is not particularly interesting or relevant to them. The immediacy of the visual can be a powerful vehicle through which to teach argument.

In a recap of a conference on nuclear arms at the Wingspread Conference Center in Racine, Wisconsin that took place in Dec. 1983, Marian Rice writes about the inevitability of the intrusion of visual consideration into the argument on nuclear arms: "Richard Ringler, University of Wisconsin-Madison, demonstrated audio-visual material she has developed to show how the themes of war and peace have been treated in art, literature, and music. He stressed that it is necessary to approach nuclear weapons issues from a variety of viewpoints in order to reach students who might feel they do not have the background for a course which deals with technical topics" (8). Thus, the argument regarding nuclear technology might serve as an appropriate case study for the way in which visual rhetoric works as an effective accommodation to the ever-evolving needs of society at large. Whether one is utilizing visuals, art, literature, video, or some other medium, the function of argument can still work effectively. We should think of visual rhetoric not as a replacement of traditional argument, but as a complement to it, as a way of encouraging our students to think critically about a topic, even if they feel it is not particularly interesting or relevant to them. The immediacy of the visual can be a powerful vehicle through which to teach argument.Work Cited

Rice, Marian. "Conference on the Role of the University in Addressing Nuclear Weapons Issues." Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 37.6 (1984). JSTOR.

Photograph courtesy of www.neatorama.com

Comparative nuclear theory, set to music

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=51AX47SYVEo

The above video clip is a collage of nuclear test explosions set to the heady, intense rock 'n roll of P.O.D., a pseudo-hard core band. The images, synthesized with the musical intensity, seem to evoke feelings and images of power and control. While it's difficult to judge whether these images are pro- or anti- nuclear weapons--or neither--it is undeniable that the visuals are given a certain power by the thrash factor of the music. Now, compare that video with the following one:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLMIy_sSZJQ

This video, set to the music of Celine Dion's "My Heart Will Go On," might be satiric on the part of the video creator, but it cannot be denied that these images certainly possess a much more serene and reflective quality when put to a different soundtrack. As opposed to thinking in terms of power and control, one begins to think of nuclear technology in more existential terms. There is even an odd, paradoxical feeling of beauty when one looks at the images while listening to the song in the background.

You might be asking yourself, "What is the point of all this?" There are two points I am trying to get across here. First off, I am trying to further prove my point that visual rhetoric is an extension of the thought of argument as dialectic. We have images juxtaposed with music, and the music has a way of changing the mood that we might associate with the images. Second, I am using this discussion of nuclear technology as a way of launching into my next post about the way that much argument in today's visual age accommodates itself to visual rhetoric. But more on that later.

An inevitable return to dialectic

In Fragments of Rationality: Postmodernity and the Subject of Composition, Lester Faigley writes, "[Postmodern theorists] have shown how no theory can claim to stand outside of a particular social formation and thus any critique must be self-reflexive. In overturning notions of the self and individual consciousness, postmodern theorists stress the multiplicity, temporariness, and discursive boundedness of subject positions" (111-12). I hope that my previous visual analysis of the Triangle Shirt Waist Factory Fire has proven effective in stressing the subjectivity of argument that extends even to the medium which one uses to construct that argument. One can still manipulate the argument, whether it be through choice of photos or through the arrangement of objects within the frame, but that rhetor is still bound by the rules of logic within their own discourse to create an effective argument.

Work Cited

Faigley, Lester. Fragments of Rationality: Postmodernity and the Subject of Composition. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 1992.

Study questions for the Triangle Factory Fire topic

How did you react to the photograph(s)?

Does this photograph persuade you to think in a certain way about this issue?

What do you base this persuasion upon?

Might this photograph function as its own argument, or does it require other means to back it up?

Would the other means required to back this argument require text, numeric data, other visuals, or some other means of evidence?

How does this photograph function in a different way than other textual evidence might function?

How would you arrange these photographs so that the relationship between them forms a more effective or coherent argument?

We must encourage our students to think of photographs and the relationships between photographs as a sort of dialectical discussion, where all the pieces fit together in a cohesive and arguable way.

Rhetorical residue of the visual

The first (which is located in this gallery) depicts some of the cramped working conditions that employees in the factory were subject to prior to the fire. Let's assume for a second that a student were using this photo as part of an argument against the working conditions permitted by Blanck and Harris. This student might be arguing for tougher labor and union laws that would make space concerns like this tougher for the owners of the factory to enforce.

In my opinion, the photograph itself would serve as a fine piece of evidence of the "inhumane" working conditions at the factory. Space is clearly cramped, and the picture seems cluttered with equipment and scraps. We can see that if a major fire were to spark in this area, it might be difficult for the individuals in the photo to evacuate.

The student might be wary, however, of using this photo as a stand-alone piece of evidence. As with any piece of evidence in any primary textual argument, the photographer is free to edit and manipulate the field of view within the picture so as to "frame" a certain ideology. We have no way of knowing for certain whether or not the space that lies outside the camera frame is as cramped and claustrophobic as the area within our immediate field of vision. While the student should be encouraged to use a photographic like this as evidence, she might also be encouraged to complement it with other evidence as well, whether it be data or textual analysis.

In the second image, which is located in this gallery, we see a floor plan of the ninth floor of the factory. It is not a photograph, but it is a visual. It serves as a map, situating us geographically within the entire space of the ninth floor. This photograph might serve as a fuller piece of persuasion, a sort of complement to the previous image. Instead of being restricted by the camera's field of vision, as we were in the first photograph, we are given a more panoramic view of the floor. We see how close together the tables are situated, and how their length would make it difficult for workers to file out to the aisles and evacuate in the case of an emergency. We see how the exists are not easily accessible for those workers who might be in the middle of the room. This visual would serve as a fine justification of a student's theoretical claim that conditions within the factory were too cramped.

People who claim that the working conditions at the Triangle Factory were inhumane and did not accommodate evacuation procedures assert as part of their argument that the stairwells, in addition to being difficult to access, were much too narrow in order to facilitate mass evacuations. For those who make this claim, the fourth photograph in this gallery would be an especially appropriate piece of evidence--though it would likely require some explanatory text accompanying it. Here, we see that the staircase is quite narrow and winding in awkward places. The doorway is probably too narrow to accommodate a large number of people attempting to get out in the case of a fire. As I mentioned, though, the rhetor/student would probably want to provide some text in a caption explaining the context of the photograph. It would probably not be sufficient enough simply to place this picture in a visual essay without giving the contextualizing explanation that I just provided.

I bring up a couple of the photographs in this gallery, which depict unidentified bodies lined up in caskets for people to view, for a couple of reasons. First, they carry with them a powerful emotional resonance. The mere image of bodies lined up in a row, lying in a dank warehouse in the aftermath as people attempt to identify the remains has a powerful pathos element to it. A photograph like one of these might serve as a powerful contextualizing piece setting up the rest of a student's argument. The reader/viewer would immediately be immersed into the gripping context of the subject matter. However (and this is the second reason that I chose to include this photograph), I believe that a photograph like this reveals some of the danger of the misapplication of principles of visual rhetoric. If one were to use this photograph or one strikingly similar to it as her main piece of evidence to prove that the working conditions were inhumane, she might inadvertently begin to ignore the logos stem of argument as a result. The reader/viewer might develop a profound emotional attachment to the incident at the expense of the hard data associated with the incident. A student might attempt to prove her argument solely on the basis of emotionally wrenching photographs such as these without considering other factors, and then the argument becomes pure emotion. The immediacy of the visual to the mind would become a danger then, and, as with any other traditional form of argument, inaccurate and misleading manipulation might take precedence over the unity of the logos, pathos, and ethos stems of argument. The student would want to be very careful to complement an image such as this either with written text or with some other photographs, like the ones I already addressed, so as to develop a fully unified argument.

The Triangle Factory Fire as a subject for visual argument

The Triangle Factory Fire has lent itself over the years as a stimulant to argument over work conditions both in America and abroad. The work conditions that led to the fire and to the deaths of 146 people might be described today as "sweat shop" conditions, and this is one of the reasons that its (tragic) legacy continues to live on today in sociological studies, visual analysis, and literature. Workers in the factory made women's blouses and were subjected to generally claustrophobic work conditions. The floors on which they worked were crowded and dimly lit, according to Jason Zasky: "[...] the co-owners of the Triangle Waist Company, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, viewed their employees as nothing more than disposable parts in a giant profit-making machine. If workers griped, their concerns were likely ignored" ("Fire Trap"). Blanck and Harris's business was threatened several times by a union labor strike, but according to Zasky, a number of workers counted themselves fortunate in their work situation, because the ceilings were high, the windows large, and the technology cutting-edge, among other factors. The factory, however, was infamous for a number of minor fires that were easily put out.

One day, however, one of the fires quickly sparked out of control, leading to panic: "The workers had always been able to contain small fires and this one—most likely started by someone dropping a match or a lit cigarette into the bin—probably looked no different. But this one was different, and fueled by highly flammable cotton fabric strips, it quickly raged out of control" ("Fire Trap"). As mentioned earlier, 146 people died trying to evacuate the building, and this led to serious discourse on work conditions.

In his article titled, "The Triangle Shirt Waist Factory Fire of 1911: Social Change, Industrial Accidents, and the Evolution of Common-Sense Causality," Arthur F. McEvoy writes,"In a symbolically powerful way, the Triangle fire wrote out the power of employers to extract wealth from their workers on the bodies of the victims themselves, in public" (630). It is the functionality of this social event as a "symbol" that I am particularly interested in. As I intend to explore in later posts, the symbolism of visuals, as well as the rhetorical evidence that these symbolic visuals evoke, should provide a powerful avenue for the accessibility of argument in a way that mere text cannot produce in such an immediate way. The photographs that both expose the poor work conditions and provoke an emotionally jolting resonance for the audience of an argument have proven especially effective for the continuing of discourse on the subject.

Works Cited

McEvoy, Arthur F. "The Triangle Shirt Waist Factory Fire of 1911: Social Change, Industrial Accidents, and the Evolution of Common-Sense Causality." Law & Social Inquiry 20.2 (1995). JSTOR. 20 November 2007.

Zasky, Jason. "Fire Trap: The Legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire." Failure Magazine. 20 November 2007. http://www.failuremag.com/arch_history_triangle_fire.html.

Friday, December 7, 2007

The metaphor of the rhetor

In "The Rhetorical and Metaphorical Nature of Graphics and Visual Schemata," Rosemary E. Hampton works to justify the dialectical mechanism of visual rhetoric by claiming it as an extension of rhetoric's metaphorical form. She writes, "Rhetoric cannot escape metaphor. [...] Because metaphor is a means of regulating the world of thought, cognition and interpretation require knowledge of codes used in different symbol systems--the symbol systems in the technologized context of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries" (348). If we are to think of rhetoric as the manifestation of a dialectical search for meaning or reality, then that manifestation signals the rhetorical form itself as a metaphor for the search for meaning that occurs inside of the individual's mind. This postmodern conception of argument emphasizes the style and form of the argument as well as the actual content of the argument. If the form of the argument is to carry a significant amount of weight in the articulating and persuasiveness of the argument, then the accommodating of the argument to modern means of communication becomes a valid concern for the rhetor.

Here, one might begin to think of the place of visuals in the argument, whether they are used as pieces of evidence in themselves or whether they are used as mere stimulants and entry points into the argument itself. In following posts, I will explore the Triangle Shirt Waist Factory Fire, the visuals associated with it, and the roles of the visuals in the context of the argument.

Work Cited

Hampton, Rosemary E. "The Rhetorical and Metaphorical Nature of Graphics and Visual Schemata." Rhetoric Society Quarterly 20.4 (1990). JSTOR. 1 December 2007.

Thursday, December 6, 2007

In Rhetoric: Concepts, Definitions, Boundaries, William A. Covino and David A. Jolliffe write, “Rhetoric is not dialectic, although Aristotle calls rhetoric the antistrophos (counterpart) to dialectic, and the examples from Plato and Berthoff above suggest that rhetorical explanation can take on a dialectical—question-answer or comment-response—form” (8). While Covino and Jolliffe’s essay does not directly address the concept of visual rhetoric and the various modes or forms which argument might take, I think their link between rhetoric and dialectic is an appropriate locus point around which to construct the central theme of this project: visual argument and the teaching of it to college students. The interspersing of visuals/photographs with written texts creates an argument that is directly dialectical not only in the content of the argument itself, but also in the form the argument takes. In a very simplistic sense, one might say that the exchange between visuals and text or other modes of discourse serves as an extension—or metaphor—of the dialectical exchange of ideas within the framework of the argument itself. It is for this reason—the instilling in students’ minds of argument as dialectical—that I believe the pedagogy of visual rhetoric is crucial for the college composition teacher to consider.

The danger that emerges in the teaching of visual rhetoric without teaching the basic principles of ethos, logos, and pathos, is that students may begin to let the emotional pull of images supersede the logos of the argument, so that a visual argument might become a collage of sentimental images and symbols so connected with the bathos of emotion that it does not carry any actual logical weight at all. This brings me to another purpose of this blog: to explore ways of teaching visual rhetoric so that it complements—rather than replaces—the traditional methods of logical arguments that have survived through the ages.

Work Cited

Covino, William A., and David A. Jolliffe. Rhetoric: Concepts, Definitions, Boundaries. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1995.